Last week, on one of those days of living from hand to mouth like a peasant after a bad harvesting season, I pulled up at a fuel station and ordered 20 litres worth Ush100,000.

Last week, on one of those days of living from hand to mouth like a peasant after a bad harvesting season, I pulled up at a fuel station and ordered 20 litres worth Ush100,000. I picked up the phone to initiate payment, but my balance was zero. A prompt to take a quick loan came, but I was only eligible for Ush20,000, yet the pump attendant had already dispensed all the Ush100,000 worth.

I told her my crisis but, unbothered, she asked for my phone, punched some digits and told me to enter my password. I did and she smilingly waved me off, reminding me to pay soon as the facility she had used levied harsh fines for late payments.

I read the transaction report; it was yet another mobile loan product I hadn’t yet heard of, operating on my telecom service provider’s platform.

I began fearing that easy credit, which trapped western consumers into regimented existence where individuals surrender their financial planning to invisible systems, but the scales fell off my eyes.

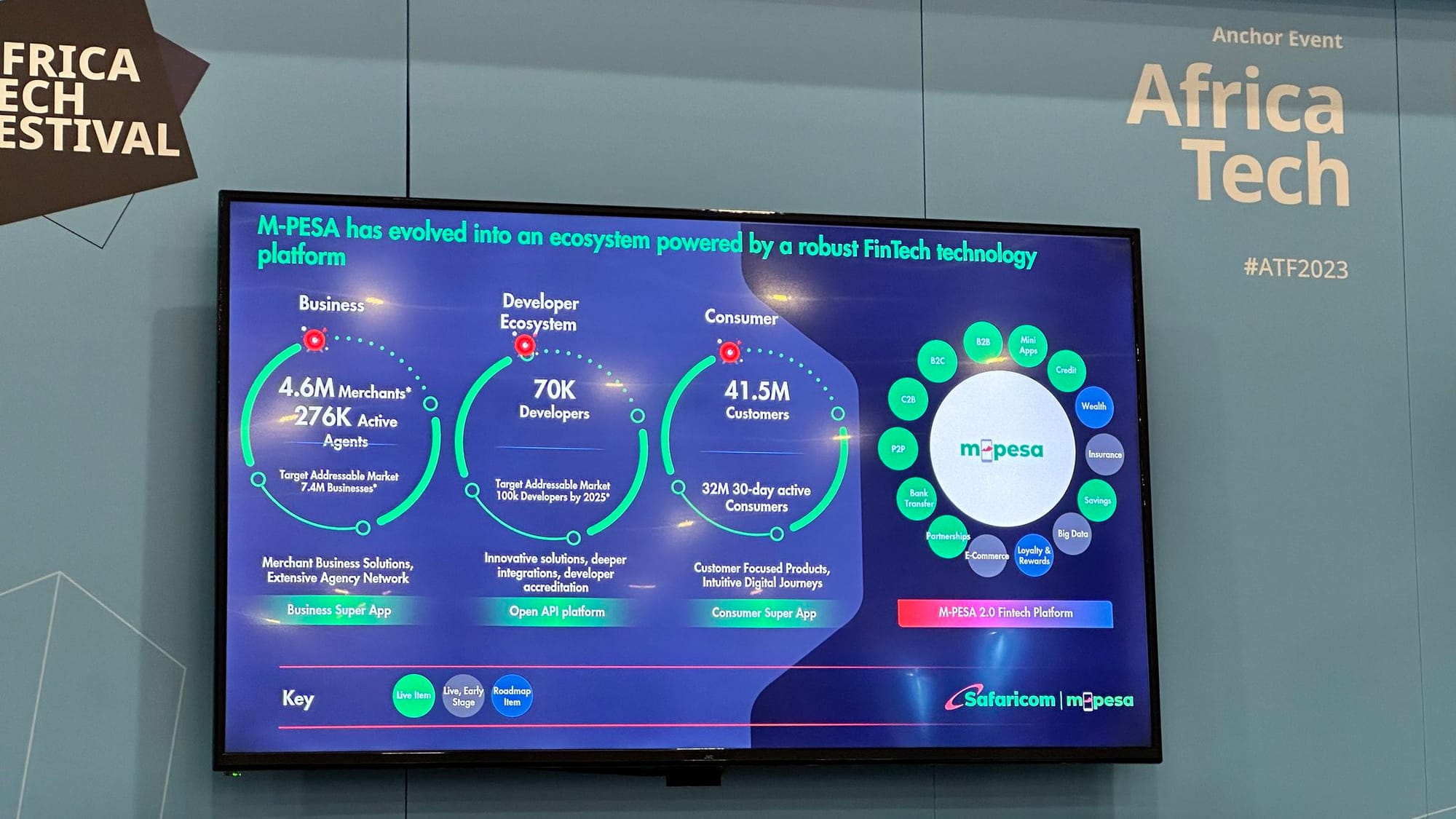

Read: Africa leads in mobile money growthAfter a century-plus of economic colonisation, Africa now seems to have the tool for financial liberation in its hand. And it wasn’t rconomics professors, but small traders who discovered the potent tool.

How many citizens in an African country had ever made an instant non-physical money transfer at the turn of the century 25 years ago? One percent? Probably less.

A credit card was not even a status symbol for it was a secret possession very few had. ATM/debit cards are common but they are just that — a tool for picking your cash from a hole in the wall — at a fee.

Electronic money transfer had to be done in a bank through a tedious process. For long, a bank wasn’t a place for simple citizens to enter; today you don’t need to enter a bank at all.

Then, banks in Uganda were mostly foreign — and still are. Only one in eight banks is local, and a relentless drive to close down local banks has been underway for four decades.

Generally, our commercial banks hate lending to local customers, seeing them as risky, and prefer investing their deposits in government paper, which guarantees them double-digit profits at zero risk.

Beyond being centres for workers receiving monthly salaries, banks mean little to Ugandans who aren’t in business, including the 500 top national legislators.

Our banks punish you for depositing your savings with them by charging you fees to save, so your money becomes less even if you don’t touch it.

Our banks have, for decades, been charging interest on loans at four-to-six times higher than the annual inflation rate. They remain largely punitive neocolonial institutions.

After mobile phones came to Africa three decades ago, telecoms were still focusing on selling voice call services when small traders in poorer countries, where commercial bank branches hardly existed and electronic money transfers were little known, saw an opportunity.

The traders started buying airtime scratch cards and sending the number by text to faraway beneficiaries, who would redeem the number into cash at an airtime dealer. And hence mobile money was born.

Telecom companies’ IT experts refined the process whose creation, in all honesty, should not be claimed by any individual or company.

The last to wake up were the economic policy leaders who then got central banks to become mobile money regulators instead of the communications regulators.

Today, mobile money is the most potent weapon to secure Africa’s economic development and, hopefully, this time policy makers won’t take long to wake up.

Read: MTN to split mobile money from its core businessFigure this: This financial year, MTN Uganda alone is expected to handle more money than the total value of the country’s entire economy. And, yes, the same telco has finally democratised the financial markets, especially treasury bonds, which had, until recently, been a preserve of the elite — including those who dip into the public purse and need to launder their loot.

Now, MTN has opened for the market woman and boda boda rider to invest in unit trusts daily. Imagine that! From losing money by saving it in a bank to earning over 10 percent compound interest by investing your three dollars daily using your phone.

It would take deliberate negligence for governments to run to foreign lenders before considering borrowing from their own people.

Today, lazy African government economists and their masters in foreign lending institutions quickly sign loans knowing there is no capacity to pay, thus enslaving the young and the unborn Africans.

Now, mobile money is showing that there are enormous resources within the people, readily available to a borrower who is willing to pay.

Mobile money is unlocking Africa’s wealth for development. Will African economists continue choosing irresponsible borrowing that ends in economic slavery? Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (Syndigate.info).

Post a Comment